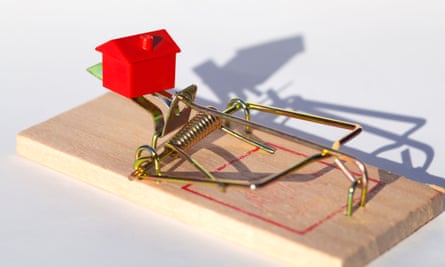

Young people drowning in debt: ‘Don’t borrow your way out of a recession’

Everything has been going right for Tash Drujinin of late.

A few months ago the 29-year-old landed a stable job in the financial services sector. When many thousands were being laid off with the pandemic, she was made permanent and the security meant she could finally pay off the $20,000 she owed in credit card bills and personal loans.

It had been a long time coming. As the country celebrated nearly three straight decades of economic prosperity, Drujinin had fallen into debt in her early 20s to finance her escape from family violence.

While Centrelink refused her application for social security, her bank was willing to approve a $15,000 platinum card with a 19% interest rate for the “barely employed” university graduate. That debt would end up costing her thousands in interest payments and, as she sees it, a decade of her life.

It was as though we learned nothing from the global financial crisis. We’ve learned nothing from the royal commissionTash Drujinin

She says her “lost decade” slowed her whole life down as she had to find a way to pay back the money.

“It’s really hard to explain to people what that feels like,” Drujinin says. “It’s not like there’s a name for the situation you are in. There’s no disease or illness that says why your life is like that.

“You don’t stop thinking about it. It creates anxiety and it becomes debilitating. It impacts every single aspect of your life. You get into the car, the check engine light comes on, or the fuel light is on. Then you start negotiating with yourself about what your priority is going to be.

“And you know, a lot of people out there have it worse than I did.”

‘One of the lucky ones’

Today Drujinin feels like one of the lucky ones – especially now the Morrison government is talking about winding back responsible lending laws.

In September the government announced it was looking to debt-finance an economic recovery by making it easier for people to get loans with fewer checks. This move would coincide with other efforts to wind back economic supports and plunge social security payments back down to levels well below the poverty line.

Drujinin says that means bad news for those now entering their 20s.

Frydenberg’s move to dump lending laws ‘shortsighted’, consumer groups sayRead more

“It made me so mad that when I first read about it,” she says. “I almost took it personally. It was as though we learned nothing from the global financial crisis. We’ve learned nothing from the royal commission.

“I’m in a better place now, but what about the other young women in their 20s coming up?”

When the relaxation of lending rules was announced in September last year, treasurer Josh Frydenberg – and the Reserve Bank of Australia – pitched it as a measure to “cut red tape”.

“As Australia continues to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, it is more important than ever that there are no unnecessary barriers to the flow of credit to households and small businesses,” Frydenberg said.

“Maintaining the free flow of credit through the economy is critical to Australia’s economic recovery plan.”

Australians have huge household debt

Under the government’s proposal, the National Consumer Credit Protection Act would be changed to allow lenders to give out money without thoroughly checking whether the borrower could afford to repay the loan.

The proposal directly contradicted the first recommendation of the banking royal commission that called for the provision to be left alone to prevent the same predatory lending that initially triggered the inquiry.

“The NCCP Act should not be amended to alter the obligation to assess unsuitability,” the report said.

Australians are already some of the most indebted people on the planet.

The latest OECD figures show the ratio of Australian household debt to net disposable income stands at 217% – meaning the average household owes twice what it makes in the year. Measured relative to GDP, the Bank of International Settlements puts Australian household debt at 119% – second only to the Swiss.

View image in fullscreen‘Many young people will find themselves weighed down by a constellation of personal credit arrangements – credit cards, overdrafts, payday loans, outstanding bills, fines and Afterpay-style arrangements.’ Photograph: Stephen Coates/Reuters

View image in fullscreen‘Many young people will find themselves weighed down by a constellation of personal credit arrangements – credit cards, overdrafts, payday loans, outstanding bills, fines and Afterpay-style arrangements.’ Photograph: Stephen Coates/Reuters

While much of this debt is generated by the housing market, the situation for young people is more complicated. As they are less likely to own assets, many will find themselves weighed down by a constellation of personal credit arrangements – credit cards, overdrafts, payday loans, outstanding bills, fines and Afterpay-style arrangements.

Though there is a perception that young people are simply bad at handling their money, an Asic investigation found that wasn’t necessarily true. In a reflection of the circumstances faced by many young Australians, when the regulator looked closely, it found young people were less likely to hold a credit card but were both more likely to get into trouble when they had one, and were more likely to hold multiple cards.

Since the pandemic, the response by young people and their parents has been marked. Australians broadly responded to the crisis by paying down debts or closing accounts – 70,000 credit cards were chopped up between August and September alone.

I do not want to get caught in the benefit trap. I want to work | Jake TurnerRead more

Young people, however, have been more likely to fall further into debt as they seek to refinance existing loans or take out new personal loans to get by.

A report by the Consumer Policy Research Centre says one in 10 young people reported taking out a personal loan in October, up from one in 50 in May, and one in five said they had relied on more informal lines of credit, such as borrowing from family members.

The centre’s chief executive Lauren Soloman warned of exploitative lending practices and said: “Young people particularly are at high risk of drowning in debt, from which it may take a lifetime to recover.”

Don’t borrow for essentials

Gerard Brody of the Consumer Action Law Centre says: “I think this will have a big impact on people’s mental health, living with this financial insecurity over their heads. That in turn has an impact on a young person’s ability to hold down jobs, see friends, maintain their mental health. It feeds into everything they do.

“If we actually wanted to create financial wellbeing, the first principle, the simple advice is: you shouldn’t be borrowing for essentials.”

Danielle Wood, chief executive of the Grattan Institute and co-author of a 2019 report that mapped the breakdown of the intergenerational bargain within Australia, says it should not surprise anyone that young people were turning more to personal loans.

“It’s not surprising that we see more young people in financial distress and resorting to debt finance than other groups,” she says. “People under 30 lost jobs at more than three times the rate of other groups during the lockdown.

“For those 20 to 29 years, jobs are still down close to 10% on March levels. Young people were also more likely to miss out on jobkeeper because they are disproportionately short-term casual workers in the hard-hit sectors.

More debt is not the answer to financial difficultyFiona Guthrie

“So you have more young people trying to live off what is again a below-poverty line jobseeker payment. The problem will get worse for those that don’t find a job before January.”

As of December there were still 959,400 Australians out of work.

This reality for young people is set against an already bleak backdrop captured in two reports from the Productivity Commission released in June and July. They showed how those Australians who had come of age since the 2008 global financial crisis have seen their incomes decline by 2% and found themselves locked in to more unstable, more insecure jobs over time.

University of Queensland economist John Quiggin says this makes the issue not just one of age, but also of class.

“It’s not all one, or the other,” Quiggin said. “The process by which young people establish themselves as independent adults has been getting harder over time. This has been going on for a while, but some also have access to the bank of mum and dad.

View image in fullscreen‘The situation where a young person can save to get a deposit and go by a house independently of their parents is becoming more and more difficult.’ Photograph: Alamy

View image in fullscreen‘The situation where a young person can save to get a deposit and go by a house independently of their parents is becoming more and more difficult.’ Photograph: Alamy

“The pandemic has accentuated things that have been going on since the GFC, particularly for young people. The situation where a young person can save to get a deposit and go by a house independently of their parents is becoming more and more difficult.”

Unfortunately for those who are already struggling, the message from the government is that if they need help in the future, they should take out a loan.

Fiona Guthrie, chief executive of Financial Counselling Australia, believes this will only entrench inequalities by making young people’s mistakes more costly. The risks creating a self-reinforcing cycle that makes life increasingly unfair for young people without the means.

“You don’t borrow your way out of a recession. More debt is not the answer to financial difficulty,” Guthrie says. “The thing about these responsible lending laws – if they are also successful in removing the social safety net you won’t see the problems two weeks later, or two months later, but two, three, five years later, long after the politicians have moved on.

“There’s this lovely debt conveyer belt. That’s how I visualise it. On one end it’s marketing: make it as easy as possible to get debt. Then you say, ‘Well, we know some people won’t pay it,’ and when they don’t, we sell a portion of it for cents in the dollar to the debt collector.

“When that person’s done with that, they might still need money, so they go out and get another loan.

-

If you are feeling overwhelmed or need financial help call the national debt helpline on 1800 007 007.

-

Royce Kurmelovs is the author of Just Money: Misadventures in the Great Australian Debt Trap